Among the many advancements computer science has made in the past couple of decades, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the most widely known. You might have simply heard about J.A.R.V.I.S from the Avengers or smart assistants like Siri or Alexa. All of them use AI and machine learning algorithms to work as well as they do. It turns out that we can get a glimpse into one such algorithm - particularly the one used by computers to beat you at chess, connect 4, tic-tac-toe and more. It’s called the Minimax Algorithm and you can implement this by yourself very quickly. In fact, you can optimize this algorithm to run faster and more efficiently using a technique called Alpha Beta Pruning in just a few extra lines of code. Let’s see how it works.

Two player turn based games like chess, tic-tac-toe, backgammon etc, when played against a computer are based on the Minimax Algorithm. This algorithm uses backtracking to find the optimal move at any point in the game by assuming that the opponent also plays optimally. The two players are sometimes called the maximising and minimising players. The objective of the maximising player is to get the largest possible positive score or the smallest possible negative score based on board evaluations. On the other hand, the minimising player tries to get the largest possible negative score or smallest possible positive score. These scores indicate the player having the upper hand at that instant - positive for maximising player and negative for minimizing player.

The way these scores are evaluated differ in technique and complexity based on the game. For something simple like tic-tac-toe (where there aren’t too many positions to consider) we could exhaustively search all patterns until the game ends. Then the winning games could have score 1, losing games score -1 and games that draw get a score of 0. For complicated games like chess, this evaluation is a lot more involved and the number of moves is too large for us to search all positions until the game ends. So the evaluations are done considering several other metrics.

Since this is a backtracking based algorithm, it tries all possible moves from a given board position while assuming that the opponent is always going to play the best move they can. The number of moves the algorithm looks ahead is the depth of the recursion. At the end of the process, the algorithm picks the best board evaluation and makes a move intending to arrive at it. The various intermediate boards are evaluated along the way and the scores make up the decision tree of the algorithm.

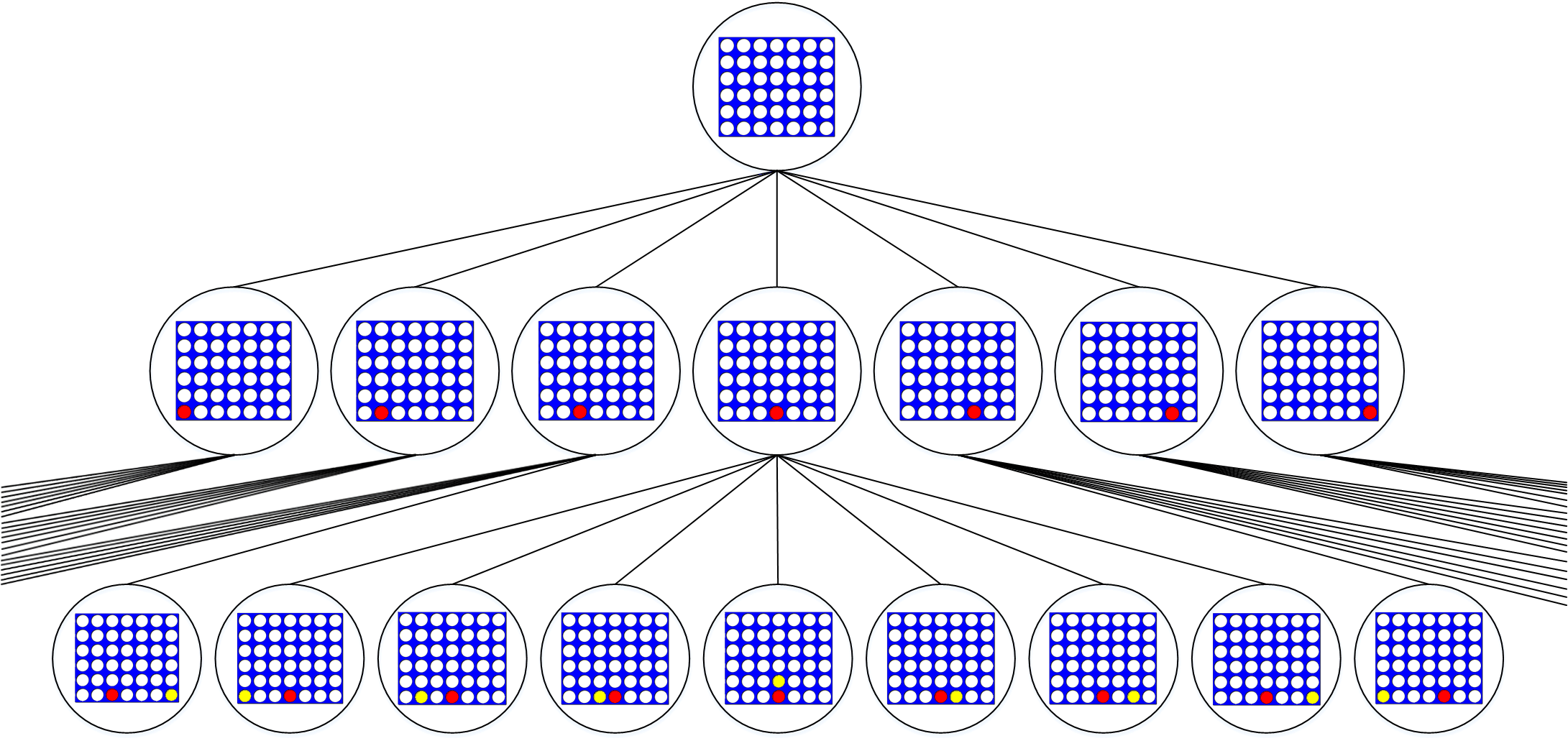

To understand what this tree looks like, consider the example of Connect 4 - a popular two player turn based game - being evaluated using minimax. Here’s a visual representation of the boards and the moves explored by the algorithm at the very beginning of the game :

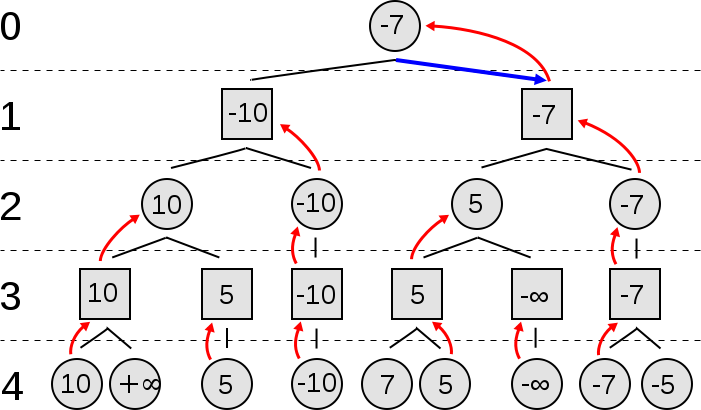

Instead, if we assign scores for each board evaluation, it could look like this:

As you can see, the algorithm tries all the moves it can make, and then all subsequent moves the opponent can make, repeatedly until it reaches the depth of its recursion. Then it picks the maximum of the branches for maximising player and minimum of the branches for minimising player until the backtracking is complete and returns the calculated value and the move/branch corresponding to it.

Here is the pseudocode for the algorithm:

function minimax(node, depth, maximizingPlayer) is

if depth = 0 or node is a terminal node then

return the score/evaluation of node

if maximizingPlayer then

best_score := −∞

for each child of node do

branch_score := minimax(child, depth-1,False)

best_score := max(best_score, branch_score)

return best_score

else (* minimizing player *)

best_score := +∞

for each child of node do

branch_score := minimax(child, depth-1,True)

best_score := min(best_score, branch_score)

return best_score

You might have already noticed that while this exhaustive search for the best result is indeed more or less foolproof, it is very time consuming and often excessive. The reason for this is because there are some moves that are so glaringly bad or some which are obviously the best ones possible and they become apparent much before the depth of recursion is reached. Unfortunately the algorithm in its current implementation cannot recognize such moves and continues its search.

To improve this, we use an optimization technique called Alpha Beta Pruning. This optimization can tell the algorithm when it has found a really good or bad move so that it can stop exploring further or to simply ignore evaluating that sequence of moves. The algorithm gets its name because it manages to shorten or prune unnecessary branches of the decision tree.

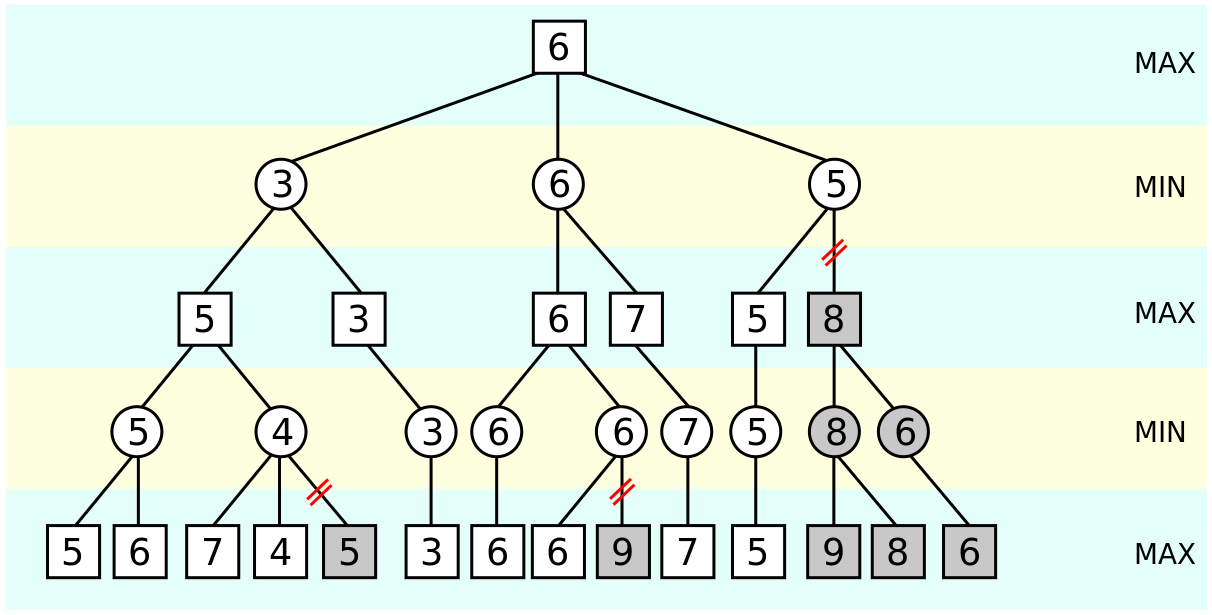

After pruning, the tree might look something like this :

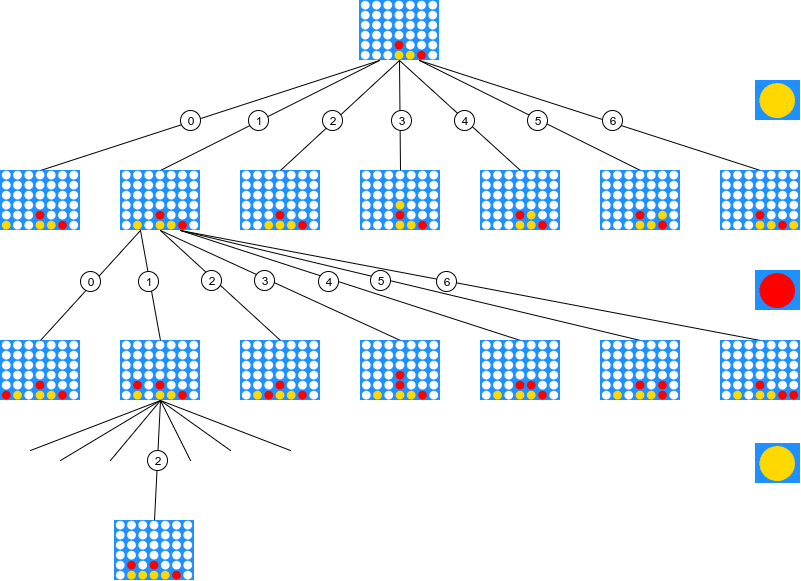

Once again, in terms of board evaluation, it could look like this:

The values seen in grey are not evaluated - those are the branches that the algorithm decided as unnecessary to explore.

This is the pseudo code for the implementation :

function alphabeta(node, depth, α, β, maximizingPlayer) is

if depth = 0 or node is a terminal node then

return the score/evaluation of node

if maximizingPlayer then

best_score := −∞

for each child of node do

branch_score := alphabeta(child, depth-1, α, β, False)

best_score := max(best_score, brach_score)

α := max(α, best_score)

if α ≥ β then

break (* β cutoff *)

return best_score

else

best_score := +∞

for each child of node do

branch_score := alphabeta(child, depth-1, α, β, True)

best_score := min(best_score, branch_score)

β := min(β, best_score)

if β ≤ α then

break (* α cutoff *)

return best_score

The variables alpha and beta are used to denote the most favourable board evaluations for the maximising and minimising player respectively. Whenever the maximum score that the minimizing player is assured of becomes less than the minimum score that the maximizing player is assured of, the maximizing player need not consider further descendants of this node, as they will never be reached in the actual play.

This optimization gives a significant boost to the standalone Minimax Algorithm but is not always bound to work. Sometimes, if the moves explored by the algorithm are just in a bad order, then it might come across one of those really good or bad moves towards the end at that level of recursion. Another unfortunate drawback of this algorithm is the fact that it cannot remember previously evaluated boards. Often we can arrive at a certain board position by performing the moves in different orders. But since the algorithm does not keep track of these boards, it re-evaluates them. In such cases, Alpha Beta Pruning hasn’t managed to reduce the number of boards that need to be evaluated.

As you can see, even with this optimization, the algorithm isn’t quite perfect. However, we can improve this algorithm further if we choose the order in which moves are explored wisely. For example, in chess, moves that capture pieces may be examined before moves that do not, and moves that have scored highly in earlier passes through the decision tree analysis may be evaluated before others. We can also consider storing some recent board evaluations (sometimes there are too many to store at once so we only consider the last few). With these, and several other improvements, this algorithm can be modified to give some fantastic results.

Alpha Beta Pruning - Wikipedia