In the last 2 years, Generative Models have been one of the most active areas of research in the field of Deep Learning. The paper on Generative Adversarial Networks (a.k.a GANs) published by Ian Goodfellow in 2014 triggered a new wave of research in the field of Generative Models. Today we'll explore what makes GANs so different and interesting.

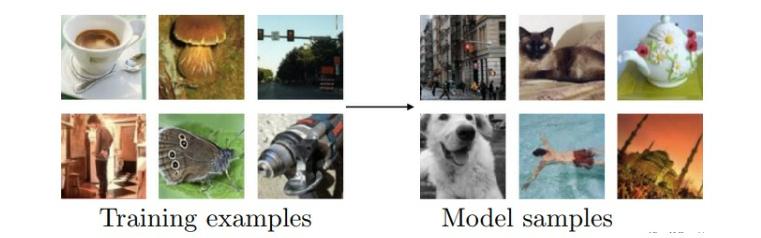

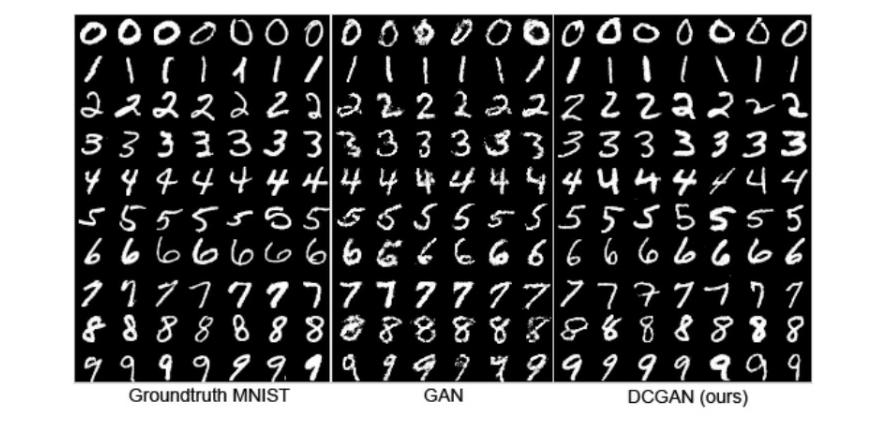

The main objective of a Generative Model is to learn the probability distribution from which the training data is sampled. Once the model learns the probability distribution, it can sample new data from it. For eg. If the model is trained on a sufficiently large dataset consisting of images of handwritten digits, we expect the trained model to then generate images of handwritten digits, which are not a part of the training data. Now, in reality, it is very hard to build models which can learn the exact probability distribution. So we usually try to build models that can just estimate the distribution or generate samples from the distribution without explicitly learning the distribution itself.

Even before the introduction of GANs, there existed several Generative Models such as Variational Autoencoders, Boltzmann Machines and Deep Belief Networks among others. But GANs provide a totally new way of building Generative Models.

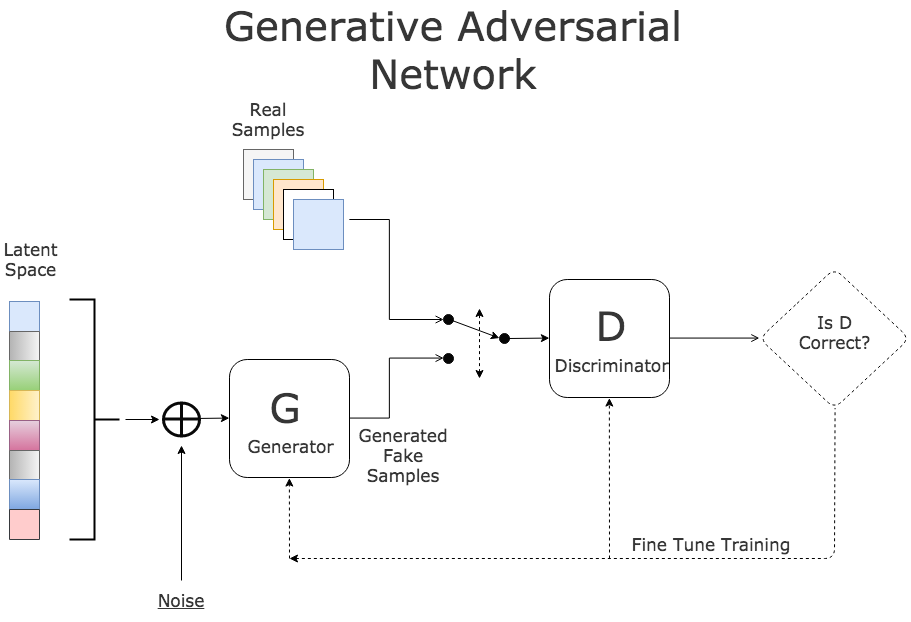

The key feature of a GAN is that the generative model is pitted against an adversary; a discriminator model which learns to determine whether a sample is generated from the model or belongs to the actual data distrubution. The generator works like a currency counterfeiter, who generates notes that are as close as possible to the original. The discriminator works as a bank that determines whether a given currency sample is fake or real. In other words, the generator tries to fool the discriminator, while the discriminator tries to prevent this from happening.

More concretely, the discriminator and generator can be represented by two separate neural networks, G and D. G takes random noise as input and outputs a sample from the learned probability distribution. D takes in a sample and outputs the probability that the given sample is real. So we would train the discriminator to maximise the probability of correctly determining whether the given sample is real or fake. Whereas for the generator we would like to minimise the probability that the discriminator correctly guesses the sample being fake. We can then determine losses for both G and D, and train them using backpropagation.

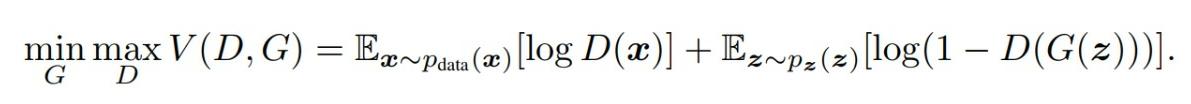

This is equivalent to G and D playing a two-player minimax game. In the ideal scenario, the generator would generate samples that are indistinguishable from the real data and the output of D would be 1/2, that is the sample is equally likely to be either real or fake.

Value function V(G, D) for the minimax game

This adversarial approach is very effective in building generative models. GANs have a number of computational as well as statistical advantages such as using only simple backpropogation to obtain gradients, no need of inferences during training among others. It also comes with its own set of drawbacks. One of them is the difficulty in training the model. The Helvetica Scenario occurs quite often during training, where the generator finds one sample which fools the discriminator, and then keeps on generating simple variations of the same sample without learning to generate other distinct samples.

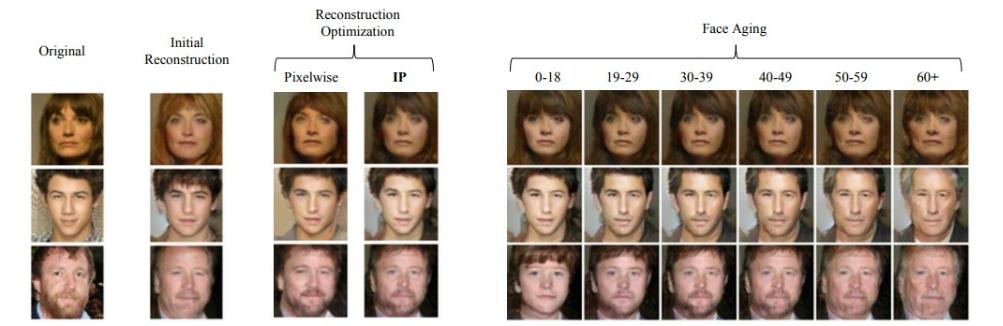

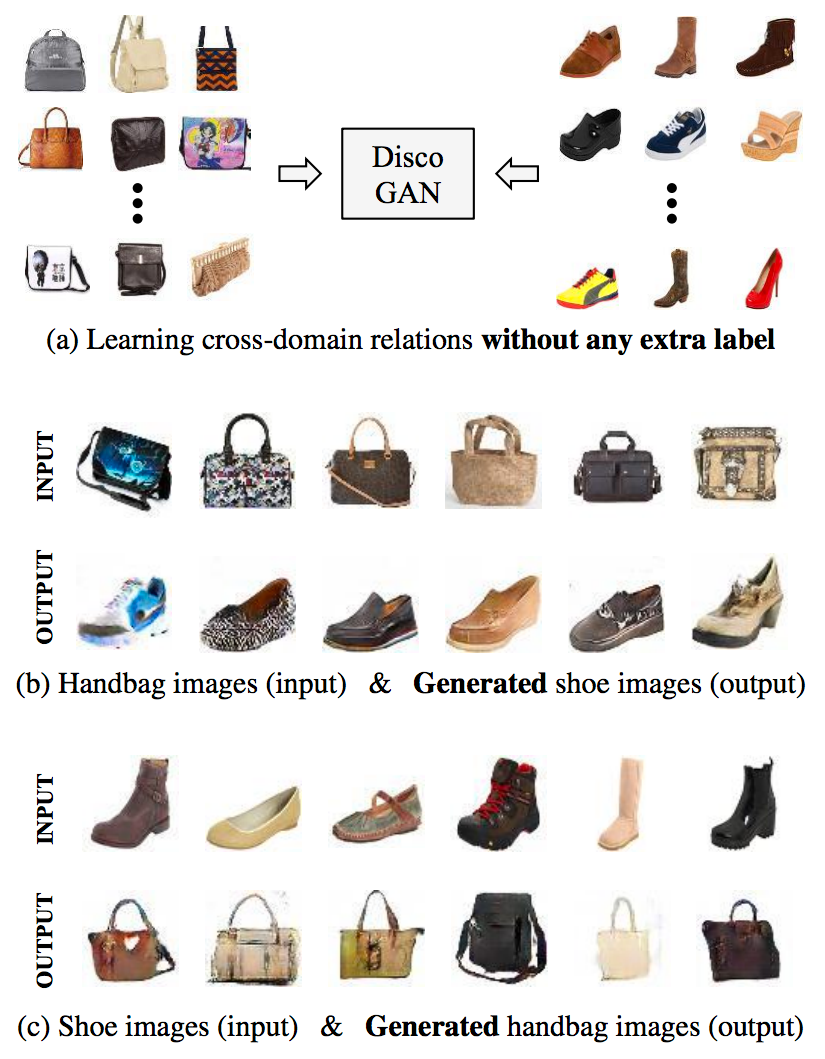

As mentioned earlier, GANs are one of the most active areas of research in Deep Learning. Hundreds of papers have been published since the original paper 2014, detailing various modifications and applications for the GAN framework. The applications range from Image to Image Translation to Image Style Transfer. Here are a few examples:

> DCGAN

> acGAN

> DiscoGAN

You can find a complete list of various GANs at the GAN Zoo