DISCLAMER: The contents on this page are strictly R rated. With R standing for Rigorous material. This is not a beginner's guide to C. This is more of an article for intermediate/advanced users to explore C, in depth. I am not responsible for any earthquakes, alien invasions or epidemics caused, directly/indirectly from this material.

Given below is a typical C program taught in most of the textbooks.

#include <stdio.h> // An include statement: Preprocessor Directive

void main() // An entry function

{

printf("Hello world\n");

}

The entire post does not even begin to comprehend the amount of work put in ,just to run a simple hello world program. To compile and run this program, a lot of juggling is done by gcc and the operating system. Of course, the standard books and online resources will tell you about how the program works, what each line is, and the technical jargon associated with them, but that is not why we are here today. Let us explore the bland hello world program and work out it's internals. I am pretty sure this will be a worthwhile trip. So hold on tight!

(Trivia: The first Hello world was written in the BCPL language and was used during the development of the C compiler, by Dennis Ritchie. Since then, the hello world program was deified by all the computer enthusiasts.)

Just to recap, here are the fundamental elements of the program:

#include <stdio.h> is a preprocessor directive.void is a data type.main() is the entry point of the program.printf() is a C function that is used to print formatted (printf - print format) strings.

Let us start unravelling some of the complexities of the example program.

The first step performed by the gcc compiler is to preprocess the source file. The compilation begins after the preprocessing is complete and there are no errors. The preprocessor directives are commands that gcc understands, and start with the symbol #. #include is a preprocessor directive that tells the compiler to include the contents of a file and paste it in place of the directive.

For example:

#include <stdio.h>

is replaced by

# 1 "temp.c"

# 1 "<built-in>"

# 1 "<command-line>"

# 31 "<command-line>"

# 1 "/usr/include/stdc-predef.h" 1 3 4

# 32 "<command-line>" 2

# 1 "temp.c"

# 1 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 1 3 4

# 28 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/bits/libc-header-start.h" 1 3 4

# 33 "/usr/include/bits/libc-header-start.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/features.h" 1 3 4

# 410 "/usr/include/features.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/sys/cdefs.h" 1 3 4

# 441 "/usr/include/sys/cdefs.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/bits/wordsize.h" 1 3 4

# 442 "/usr/include/sys/cdefs.h" 2 3 4

...

extern int fprintf (FILE *__restrict __stream,

const char *__restrict __format, ...);

extern int printf (const char *__restrict __format, ...);

extern int sprintf (char *__restrict __s,

const char *__restrict __format, ...) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__));

...

Pro Tip: Save a C file with just "#include <stdio.h>" in it. Then run `gcc -c -i <file.c> -o <file.i> to see the actual preprocessing in action. GCC's -E flag, outputs the file after performing the preprocessing. Internally, during compilation, it stores it as .i file which is later used as the input for the compiler.

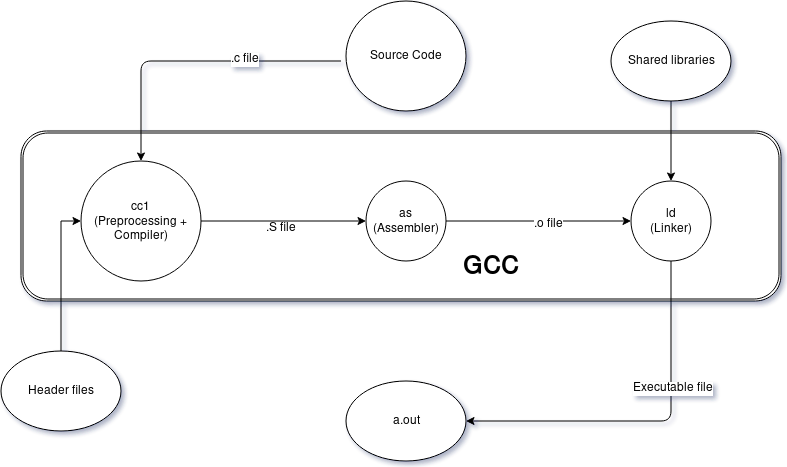

The preprocessing and compilation, both of them are done by the same program: cc1. The cc1 executable is a part of the gcc suite of programs. But, hang on! What is this <stdio.h>? Angle brackets(yeah, that is what <> are actually called. Not less/greater than symbols) tells the preprocessor that the file inside is present in the standard library path. It is usually defined in an environment variable called C_INCLUDE_PATH. You can also add directories to search for headers with the -I flag in gcc. (Example: gcc -I foo/bar <file>.c will make gcc search for .h files in foo/bar/ directory first, and then the remaining directories in C_INCLUDE_PATH). For shorthand purposes, you can write #include "foo.h" if you want gcc to add foo.h from the current directory.

We also see that printf is actually defined here. Which is why, folks! you get warnings if you use printf without including the library. But, hold on. Where is the implementation of the printf? To answer the question, please buy the full version here.

The preprocessed file is then parsed and compiled by the cc1 executable. The source code is then transformed from the C code to assembly code. All the basic data types like the void, int, char *, etc are validated by the compiler. Also, syntax checking happens here. If you enable all warnings (with gcc -Wall: Warnings-all), any compile time errors are detected here and thrown out to the user. It also checks variable usage, references and loop invariant checks too. The entire compilation consists of generating an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), and then converting it into a GENERIC format(literally). GENERIC trees are then gimplified by a gimplifier also called gimplication into GIMPLE format (Gimply, mind blowing). Then a tree SSA pass is performed. This pass performs several optimizations like:

...

and many more optimizations, each of which deserve a 15 hour course in it's entirety. (Nope, I am not going to explain them here)

.file "temp.c"

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Hello World"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

pushq %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 6, -16

movq %rsp, %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 6

movl $.LC0, %edi

call puts

nop

popq %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa 7, 8

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (GNU) 6.3.1 20170306"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

Pro Tip: Use the source code shown above. Compile it with

gcc -S <file>.c. This makes gcc to output the file after preprocessing and compiling and stops further processing of the file.

Don't worry, compilation is almost over. A step called RTL pass is performed at the end of this phase, which does some cleanup and the final assembly code is ready.

The assembling is done by the executable called as which is a part of the binutils package. This program is responsible for converting the generic assembly code into a code that is understood by the local machine. Also, ever wondered why all the C programs always start with main?

As a reward for reading the article so much, here is a nice way to write a C program without main. (WHAT?? Yes, it is possible)

#include <stdio.h> // for our beloved printf()

#include <stdlib.h> // for our beloved exit()

void _start()

{

printf("Hello world\n");

exit(0);

}

Compile it with

gcc -nostartfiles <file>.cand run./a.out

The _start program calls main internally and that my dear friend, is why C programs always begin with main.

The assembly code generated has extra elements that take care of the arguments passed to the program, the environment is setup and hard-wired to start main (or whatever entry function, if you read the article in the right order) after performing some checks. Exception handling is also done by this program. Ever wondered why only C compiled programs give segmentation fault (core dumped) errors? Wait a minute, I did not write any exception handling code. That's right. GCC adds boilerplate code that automatically terminates the program when wrong addresses are accessed and immediately packs it's stuff up, prepares a dump of the core and terminates the program.

The assembler creates an object file (.o). You can make gcc stop at this stage, by running gcc -c <file>.c. This is usually done in large projects. Multiple .c object files are created. Then they are linked together by the linker into one giant executable by the linker.

One more question, that has not been answered by our dissection so far is: Where is the implementation of printf? How come I can't see the implementation of printf?

This is done in the final phase. A basic set of shared libraries called libc, linux-vdso and ld-linux-x86-64 are attached to any basic C program. During assembly, dangling references are made to functions. Kind of like,

User: hey computer, use printf here and here

Computer: But I don't know what printf is. ERR..

User: wait, don't throw an error. I will tell you where it is, later. Just assume it is defined for now.

Computer: RRMM, oh. Okay.

The linker now points to all the dangling functions from these shared libraries. The linker fixes all references to functions. The linker is actually a program called ld, another member of the gcc core team.

Shared libraries are C programs, that are compiled before hand and can be attached to any program. There are two kinds of libraries:

1.Static libraries

2.Dynamic libraries

Nothing to be worried about. You have used both of these kinds of libraries. You just don't recognize them. Remember compiling C programs with the -lm option to enable math operations (Other examples are -lpthread, -fopenmp,etc), these are shared objects attached to the program. Shared libraries are .so files which are compiled in advance. This is usually done, in order to save memory. For example, if 20 processes are using the math library, then it is a wiser choice to seperate all the math code and leave references to it. During runtime, the process finds the required shared library in memory and resolves all the addresses.

The naming convention for shared libraries is somewhat peculiar. If the file is called libxyz.so, it has to be linked with -lxyz and vice versa.

Static libraries are just, well static. They are code, that linked during compile time. They are usually .a (archive) files. One can make dynamic libraries be attached statically into the executable by using gcc -static <file>.c -lm. [Notice the drastic increase in size of the executable output]. You can find out what are the libraries dependent on the executable by running ldd <executable>. You can also make the linker look for addition object files in other directories by using the -L flag in gcc. (Example: gcc -Lsome_dir/ foo.o bar.o where bar.o is in some_dir/)

I hope by now, you are clear on why using printf throws a compiler warning but works anyhow.

That's it folks. The C program is now ready to do your bidding. I am sure, next time someone says a "Hello world" program is easy, you can blow their brains out. Also, the programming languages evolve in a very fascinating way. For example, the token parsing program of the C code is written in C++. But C++ was written in C. This continues backwards until Dennis Ritchie first wrote C using assembly. Later C was rewritten using C. This is sometimes referred to as bootstrapping. Loading oneself using oneself. On a similar note, I hope this article stimulates the readers to read more :)