If you have written computer codes, then you certainly would have fallen into the trap of infinite loops. Then you might have wondered if there is an algorithm to check if any given computer program runs into an infinite loop or not; in other words, to check if it halts or not. How wonderful it would be if such an algorithm exists! But alas, the truth is that there is no such algorithm, not because no one has found such an algorithm yet, but because there is no way of finding such an algorithm ever.

The halting problem is the problem of determining, from a description of an arbitrary computer program and an input, whether the program will finish running or continue to run forever. Now let me define two terms- decidable and undecidable. A problem is decidable if it has a solution. If there is no algorithm that solves the problem in a finite amount of time, the problem is undecidable.

Are all problems decidable? Given enough thought, can we always come up with a well-defined procedure that takes some input and answers a given question about it? At the start of the 20th century, the belief was that this was true. Mathematicians (there were no computer scientists back then!) believed that we would eventually discover tools that we could use to answer any question we wanted (provided we could express it in the language of logic).

In 1931, Kurt Gödel shocked them all by proving that this was impossible. Using some very clever techniques, he showed that as soon as we devise a system that's sufficiently powerful and well-behaved to encompass mathematical reasoning, that system will necessarily contain a statement that we could never prove is true, even though it is true.

A few years later, Alan Turing proved an analogous theorem in Computer science. He showed that there must exist undecidable problems, questions for which there is no definable solution. His proof relied on some of the same clever techniques used by Gödel. The halting problem is one such undecidable problem

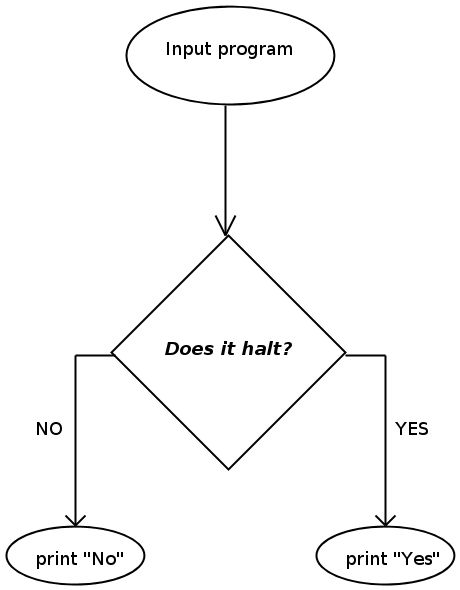

Lets say I came up with an algorithm to solve the halting problem. Then I can write a computer program for this. For simplicity, wrap this program inside a black box. Let’s call this black box - “Does it halt?”. “Does it halt?” takes a program as input and outputs “yes” if the input program halts and outputs “no” if the input program does not halt.

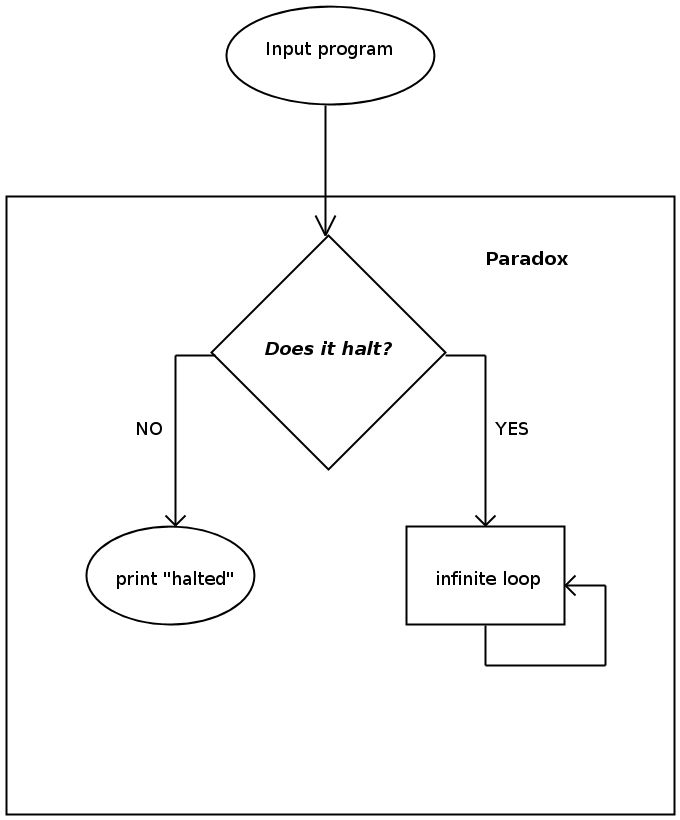

Now let me create another program that uses “Does it halt?” as a subprogram. If the output of “Does it halt?” subprogram is “yes”, then it loops forever (like a while(1){}; in C language). If the output of “Does it halt?” subprogram is a “no”, then it halts and outputs ”halted”. Lets call this new program “Paradox”.

Now here is the paradox. What happens when I input “Paradox” program to itself. Clearly one of the two things can happen: either it runs forever or it stops and outputs “halted” depending on whether the program “Does it halt?” outputs “yes” or “no”.

If “Paradox” goes into an infinite loop, it is because “Does it halt?” outputs “yes”. Since “Does it halt?” outputs “yes”, we conclude that “Paradox” halts. But this is a contradiction to the assumption that “Paradox” goes into an infinite loop.

If “Paradox” halts and outputs “halted”, it is because “Does it halt?” outputs “no”. Since “Does it halt?” outputs “no”, we conclude that “Paradox” does not halt. But this is a contradiction to the assumption that “Paradox” halts.

We have therefore led ourselves to a contradiction that “Paradox” halts if and only if it runs forever. Since this is impossible, one of our assumptions must be invalid. By tracing our reasoning backwards, we find that it is therefore impossible to have written “Does it halt?” in the first place. In other words, the halting problem is undecidable.

A lot of really practical problems are the halting problem in disguise. A solution to them solves the halting problem.